Design Thinking in Organizations

This case study and analysis was written for the Design Thinking module as part of my Master's in Digital Management at Hyper Island, Manchester (UK).

Introduction to the Case Study

This case study demonstrates how a design thinking process was implemented on a real-world design challenge by a group of students at Hyper Island and reviews the effectiveness of some of the key tools used.

Design Thinking on a Real-World Challenge

In the “Design Thinking” module at Hyper Island, full-time MA students were challenged with the following problem: “How can we improve the system, cultural and personal process to enable those people looking for gainful employment to find their success story?” Students were divided into groups of six in order to tackle the brief through a design thinking methodology. The journey below will review the author’s experience applying design thinking within a team called “d.Licious” and analyze the effectiveness of the tools used in a real world context.

The first action taken by team d.Licious was to determine which design thinking framework would drive the process. As illustrated in Figure 1 above, there are many models of design thinking. For the purposes of this brief, the team decided to use a design sprint, a process detailed and popularized by Google Ventures. A design sprint is a framework which aims to answer critical business questions through rapid prototyping and user testing and utilizes design thinking methods from places like Ideo and Stanford d.School (Google Ventures, 2016). Design sprints consist of five phases: Understand, Sketch, Decide, Prototype, and Validate.

Figure 4. Design Sprint Phases and Methods Diagram

Understand

The aim of a design sprint is to fast-forward into the future by developing a realistic prototype of a solution in order to gauge customer reaction before making expensive investments in a product. The first phase, Understand, is structured to unite the team by creating shared knowledge through an exploration of the business problem from all angles. Traditionally, there is a heavy reliance on Knowledge Experts who discuss critical aspects of the business or existing research as it relates to the challenge. For this project, knowledge experts were not readily available, as a result, d.Licious was forced into conducting secondary research and reaching out to potential experts without a guaranteed response.

The team conducted online research by reading articles, examining existing solutions, and compiling a list of potential partners in the industry. Within a short amount of time, a considerable amount of data was gathered and shared across the team. The group synthesized the data by organizing reoccurring information into themes and separating facts from assumptions. Since the provided challenge was so broad, this step was essential in helping d.Licious identify appropriate constraints, develop empathy for the end users, and reframe the design challenge into more focused “How Might We” statements.

Figure 5. “How Might We” Statement, d.Licious

Sketch

After d.Licious agreed on a How Might We statement everyone on the team was excited about, the group moved into the Sketch phase. In the Sketch phase, team members are given time and space to brainstorm solutions to the reframed challenge. The group used a variety of brainstorming tools that initially permitted individuals to produce ideas on their own and subsequently allowed the team to collectively expand on ideas with the greatest potential. Brainstorming encouraged the generation of a wide variety of unique solutions to the identified problem, and helped team members push beyond first ideas. While most of the ideas proposed in the first round of brainstorming were not great, the value of this step became apparent when everyone was encouraged to share their ideas with each other, as weird and impractical ideas led to inspiration across the team. Subsequent rounds of brainstorming became more focused as team members built on the best of each idea and crafted more defined solutions.

Figure 6. Creative Matrix for Brainstorming, d.Licious

Decide

Due to the volume of ideas the team generated, it was necessary to have a process for selecting the ideas d.Licious wanted to explore further and test. The Decide phase of the design sprint helped facilitate discussion around ideas applied to the challenge and foster consensus without significant conflict. The team used a combination of two decision making tools to evaluate ideas. First, the team used “Dot Voting” to narrow the number of solutions to the ideas that stood out and were perceived as the most interesting. Once the team had a manageable number of ideas, a “Decision Matrix” was used to give greater weight to the solutions that had the greatest potential with the least amount of effort. This quickly highlighted three unique solutions the team determined to develop and use to collect stakeholder feedback.

Figure 7. Decision Matrix, d.Licious

Prototype and Validate

The Prototype and Validate phases of the design sprint are closely coupled. In the first half, basic prototypes of an ideal solution are developed with the goal of getting an authentic response from a potential user in the Validate phase. D.Licious cycled through this process several times iteratively, focusing first on quick, sketch-based prototypes called “Storyboards” that aimed to test the team’s biggest assumptions. Since the time investment for producing multiple storyboards was so insignificant, they proved effective at quickly collecting a range of stakeholder feedback, eliminating ideas that were not feasible, and generating new insights. Importantly, they made it easier to make decisions as a team regarding which solution to commit to, and served a secondary function of aligning the team on a step-by-step map of the envisioned idea.

Figure 8. Hiring Heroes Storyboard, d.Licious

After collecting stakeholder feedback, it became clear which core solution d.Licious should pursue. However, the team was surprised to find elements of another idea received enough positive feedback during interviews that they should be incorporated into the primary solution. As a result, the team went back into the ideation process of prototyping to iterate on the leading concept. This cycle of prototyping and validation was significantly more focused, as the team had a robust foundation of primary research from interviews, and a clearer perspective of the feasibility issues faced by the stakeholders. This resulted in the agreed upon solution to pursue, Hiring Heroes, “a platform that connects businesses to nonprofits supporting the employment of people with lived experience.”

The final step was to digitally prototype the solution in order to test and refine the idea. The team prototyped the web platform and showed the concept to industry experts who interacted with the product and provided feedback. By highlighting areas of confusion and emphasizing the importance of specific features, d.Licious greatly streamlined the product, removing what was unnecessary and simplifying the minimum viable product.

Figure 9. Hiring Heroes – Home Page, d.Licious

Figure 10. Hiring Heroes – Post Job Step, d.Licious

Design Sprint Reflection

While many of the design thinking tools used throughout the design sprint proved to be useful, in the end, the team agreed that a design sprint was not the most effective framework for this particular challenge. The primary value of a design sprint comes from bringing together a cross-functional team of people. One of the most important roles in this cross-functional team is a Knowledge Expert, someone who has a particular area of expertise that is relevant to the design challenge (Google Ventures, n.d.). This is particularly important during the Understand phase where the team builds shared knowledge, establishes a shared vocabulary, and agrees on a long-term goal.

In reflection, working through a more traditional framework for design thinking that makes more room for primary research, particularly user interviews, and secondary research would have made it easier for the team to progress through the project without basing initial solutions on broad assumptions that were quickly invalidated by individuals knowledgeable about the subject.

Introduction to the Critical Analysis

This paper is a critical analysis of design thinking and the language used to communicate its effectiveness. First, the paper reviews the most accepted definitions of design thinking, and briefly reviews common themes in design thinking approaches. The paper then examines the core practical and ethical issues that undermine an organization’s ability to implement design thinking into long-term practice.

1. What is design thinking?

In 1969, Herbert Simon published his classic book, The Sciences of the Artificial, which characterized design not so much as a physical process, but as a way of thinking (Simon, 1969). Nearly four decades later Tim Brown (2008), the CEO and president of IDEO, built on this characterization, defining design thinking as “a discipline that uses the designer’s sensibility and methods to match people’s need with what is technologically feasible and what a viable business strategy can convert into customer value and market opportunity”. As a whole, design thinking is meant to encompass everything good about designerly practices (Kimball, 2011).

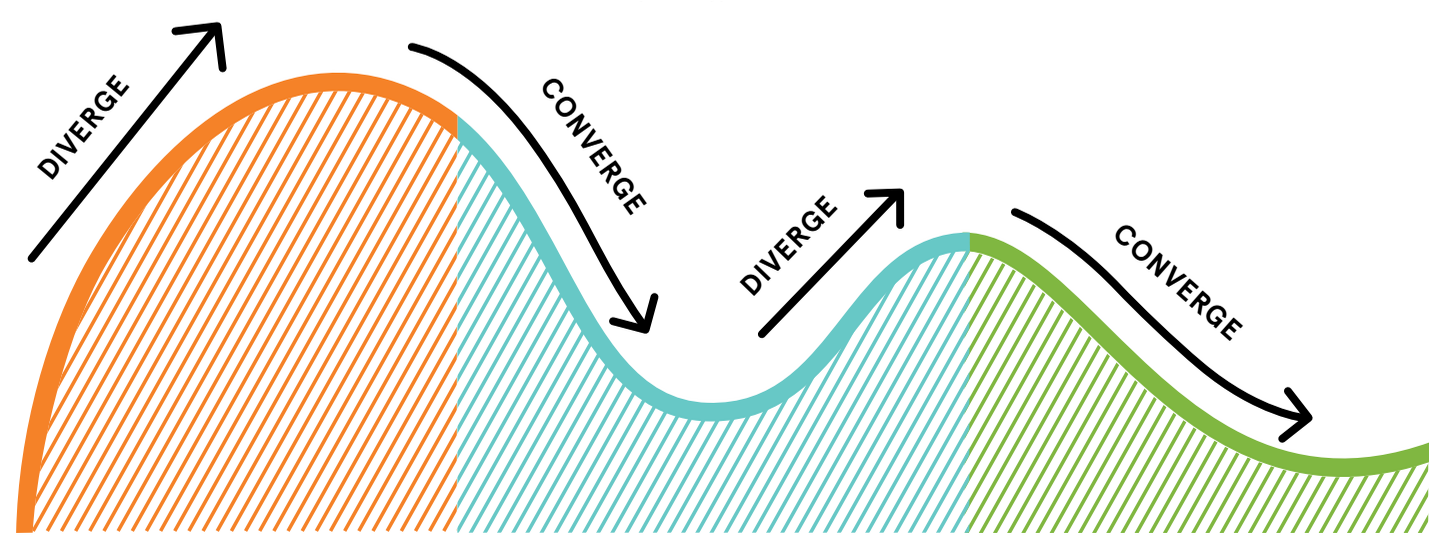

At its core, design thinking is a methodology that promises a path to innovation, and insight, through direct observation, into what people want and need in their lives. But just what design thinking is supposed to be is not well understood (Kimball, 2011). It is simultaneously defined as a mindset and a process – a split between ’thinking’ and ‘doing’ that Kimball (2011) calls the "duality of design thinking”. While there have been many models proposed for design thinking, the strongest common denominator embraces the centrality of the user and empathy to the human condition (Rodgers, 2013). Each process incorporates common design methods, or tools, for structuring thinking to deal with problems and projects (Inns, 2013). Therefore, it is helpful to examine the commonly accepted mindsets, and how they are incorporated into common design thinking practices.

Figure 1. Different Models to Do Design Thinking by Stephanie Gioia, 2011

1.1 Design Thinking as Mindsets

Most processes and methodologies used in the IT industry and business are “linear, milestone-based processes.” (Brown, 2008). In comparison, Brown (2008) describes design thinking as a “system of spaces rather than a pre-defined series of orderly steps.” These spaces, or mindsets, are where structured thinking takes place. They are described as follows:

Inspiration is defined by the circumstances that motivate the search for solutions. Teams work to identify appropriate constraints, investigate potential target audiences, and explore the contexts the new solution will be used in. Above all, close attention is given to the “extreme” users, such as children or elderly, that may benefit from the solution (Brown, 2008).

Ideation is a space for activities related to “generating, developing, and testing ideas that may lead to solutions (Brown, 2008). Design thinkers create sketches and scenarios, build frameworks out of information they discovered in the previous phase, and prototype. Customers are kept in the center of every activity.

Implementation charts the path of the solution to market. The primary concern of this phase is to design a communication strategy that makes an effective case to the business that owns the design project.

Figure 2. Three phases of human-centered design by IDEO, 2011

A typical design thinking project will start in the inspiration phase, but transition between any two of the phases is possible at any time (Brown, 2008). To give an example, while working in the implementation phase, students at Hyper Island noticed that a proposed solution to a project brief could not be adopted by end users due to a lack of access to critical technology. As a result, it became necessary to reenter the inspiration phase to collect more data about end user needs. This nonlinear approach to problem solving is one of the distinguishing factors of the design thinking approach, compared to the majority of traditional business strategies.

1.2 Design Thinking as a Process

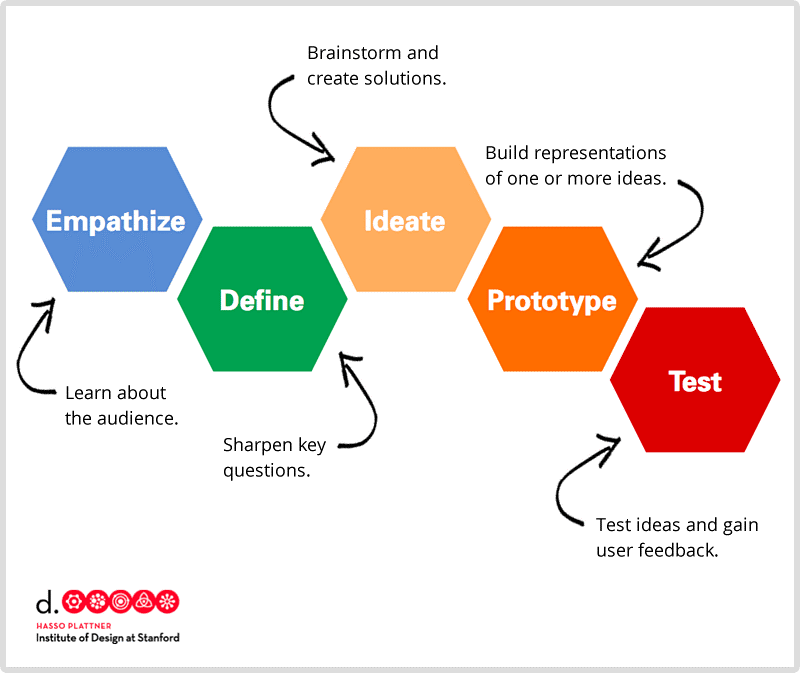

For those unfamiliar with design thinking, it is the abstract nature of this nonlinear approach that has made it a difficult strategy to implement. To make design thinking a more concrete process, David Kelley, founder of IDEO, defined five stages for the design thinking process: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test (Platner). Empathize is the work that is done to “understand people, within the context of the design challenge.” Define is sensemaking. The purpose is to “craft a meaningful and actionable problem statement” from what was learned about the user. After the problem has been defined, participants enter the ideation phase, where all actions are about finding possible solutions. In the final two stages, ideas are translated into prototypes and tested with the end users and stakeholders. In many cases, the design thinker will find it necessary to move back to one of the previous steps (Platner).

Figure 3. Stanford d.school Design Thinking Process

Kelley’s process is closely aligned with the three phase design thinking approach described by Brown. It is rare that either happens sequentially. While moving through the methods of Kelley’s approach, the design thinker necessarily moves through the three mindsets of inspiration, ideation, and implementation to deal with the defined problems, iterating as necessary. This toolkit of methods was one of the primary drivers for the adoption of the design thinking process in business environments.

2.1 Issues with Design Thinking in Practice

Descriptions of design thinking in popular literature have resulted in mismanaged expectations for business leaders, and critics are quick to describe it as a solution “over promised, under delivered.” (Thelwell, 2016). The challenges to organizations seeking to embrace design thinking are best be captured with three key points: resetting expectations, accepting ambiguity, and embracing risk.

Resetting expectations

In popular literature, it is the design thinking as ‘doing’ that has caught the attention of businesses and created a demand for “design thinking to move upstream, closer to executive suites where strategic decisions are made.” (Brown, 2011). The eagerness to adopt and apply design practices across fields has created demand for clear definite knowledge about design thinking, including a definition and a toolbox (Dorst, 2011). As a result, design thinking has become “a nice little packaged product… deployed structurally like any other business process in organizations.” (Ling, 2010).

Design thinking is a victim of its own popularity. When design thinking became popular, everyone wanted to learn it and lots of people developed an approach to teach it (Lahey, 2017). This led to many disparate, vaguely creative activities to be combined under the label of ‘Design Thinking’ (Dorst, 2011). For the sake of communication, design thinking became defined as A followed by B followed by C, but this linearization is an oversimplification (Lahey, 2017). This has created the popular perception that design thinking is mechanistic, limited in its application, and has overzealous claims on its impact (Docherty, 2017). Designers are now dealing with the misunderstanding of overselling design thinking (Thelwell, 2016).

Accepting ambiguity

Another area of tension is the lack of clear definition or consistent application of design thinking (Docherty, 2017). Much of product design is emergent, and thus pretty untidy (Wodtke, 2017). It is best understood as a complex and nuanced approach, rather than a checklist of executable tasks (Lahey, 2017). Design thinkers that have not been classically trained in design doing might be missing that great innovative solutions do not come at the end of the process; the innovation can come from any part of the process (Ling, 2010).

In addition, there are issues with translating thinking into doing. Even with the concrete implementation of the design thinking methodology realized in the Human-Centered Design Toolkit by IDEO.org (2011), novice practitioners can get stuck in “the fog,” and end up feeling lost in the process (Nessler, 2016). “The challenge is to design methods that can first of all be rapidly absorbed by a non-specialist audience – but they must also be able to structure thinking and capture ideas.” (Inns, 2013). Since the methods have to be communicated in a language that business can understand, design thinking has evolved to meet business thinking, and started to inherit the problems that business organizations wanted to move beyond (Ling, 2010). If design thinking is hastily and inexpertly implemented by individuals with an incomplete understanding of its principles, it is likely to be a waste of energy and time (Lahey, 2017).

Embracing risk

Critical insight, sensitivity to consumer needs, and innovation comes from the creative chaos encouraged by an open process. That is put in jeopardy when a traditional business mindset requires design thinking to have structure, repeatability, and reliability (Ling, 2010). Executives that are used to relying on data to gain insight into the world ‘as it is’ frequently become uncomfortable with the difference between scientific data and design, and may abandon truly novel solutions to complex problems. This is central to the paradox of implementing design thinking in business – “the results of design do not have to be repeatable, and, in most cases, must not be repeated.” (Cross, 2001).

2.2 Ethical Issues in the Adoption of Design Thinking

The current popularity of design thinking is also at the core of its ethical issues. Discussion of the practice in popular articles is viewed as “fetishistic, and limited.” (Merholz, 2009). Yet, it has driven unprecedented demand for design talent across the globe, without a clear plan for what to do when the new supply of design jobs no longer exists (Wilson, 2014). Business value of design thinking must be proven and sustained in order to keep the thousands of new designers on company payrolls. In the meantime, the agencies that used to be the primary source of design jobs are being acquired by large organizations, or no longer exist because their clients have built in-house design teams (Thelwell, 2016).

Another key ethical issue is the increasing complexity of modern design problems. At the core of design thinking are concepts such as embracing ambiguity and failing fast (Docherty, 2017). Designers are tasked with moving fast and breaking things. However, design problems associated with sectors such as public health are akin to engineering issues where lives are at risk. If something breaks, people die. Mike Monteiro (2018), head of Mule Design, and a frequent spokesperson on ethics in the design community, suggests we “ought to need a license to solve [these complex problems].” The potential benefit in these at-risk sectors will rely on a common language, clear guidance, and processes for implementation (Docherty, 2017). To reach this level of consistency within design, and more specifically, design thinking, it may be necessary to develop a system to grant professional licensing.

Summary

The goal of design thinking is to unlock untapped value through innovation. The popular literature that crosses the desks of executives in charge of making strategic decisions on behalf of businesses is often misleading, creating unrealistic expectations about the benefits of design thinking as a stand-alone practice. However, as part of a holistic design-centric culture that includes experienced design experts, fosters knowledge sharing, and promotes efficient experimentation, design thinking offers an opportunity to create value through strategic problem-solving and a more empowered and engaged workforce.

References:

Brown, Tim (2008). Design Thinking. Harvard Business Review 86(6), pp. 84–92.

Brown, T., and Katz, B. (2011), May. Change by Design. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(3), pp.381-383.

Cross, N. (2001), May. Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline Versus Design Science. Design Issues, 17(3), pp. 49-55.

Docherty, C. (2017), October. Perspectives on Design Thinking for Social Innovation. The Design Journal, 20(6), pp. 719-724.

Dorst, K. (2011), November. The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Design Studies, 32(6), pp. 521-532.

Google Ventures. (n.d.). Design Sprint Kit. [online] Available at: https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/ [Accessed 27 Apr. 2018].

Google Ventures. (n.d.). Design Sprint Kit – Frequently Asked Questions. [online] Available at: https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/ [Accessed 28 Apr. 2018].

Inns, T. (2013), June. Theaters for Design Thinking. Design Management Review, 24(2), pp. 40-47.

Kimbell, L. (2011). Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I. Design and Culture, 3(3) pp. 285-306.

Lahey, J. (2017). How Design Thinking Became a Buzzword at School. [online] Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/01/how-design-thinking-became-a-buzzword-at-school/512150/. [Accessed 19 Feb. 2018].

Ling, B. (2010). Design Thinking is Killing Creativity. [online] Available at: https://www.futurelab.net/blog/2010/03/design-thinking-killing-creativity. [Accessed 20 Feb. 2018].

Merholz, P. (2009). Why Design Thinking Won’t Save You. [online] Available at: https://hbr.org/2009/10/why-design-thinking-wont-save. [Accessed 19 Feb. 2018].

Monteiro, M. (2018). Design’s Lost Generation. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@monteiro/designs-lost-generation-ac7289549017. [Accessed 19 Feb. 2018].

Nessler, D. (2016). How to apply a design thinking, HCD, UX or any creative process from scratch. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/digital-experience-design/how-to-apply-a-design-thinking-hcd-ux-or-any-creative-process-from-scratch-b8786efbf812. [Accessed 23 Feb. 2018].

Platner, H. An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE. [online] Available at: https://dschool-old.stanford.edu/sandbox/groups/designresources/wiki/36873/attachments/74b3d/ModeGuideBOOTCAMP2010L.pdf [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

Rodgers, P. (2013), July. Articulating design thinking. Design Studies, 34(4), pp. 433-437.

Simon, H. (1969). Science of the Artificial. Cambridge: MIT Press

Thelwell, C. (2016). Design thinking: an over promise under delivered. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/think-big-work-smart/design-thinking-an-over-promise-under-delivered-ad81b1318aa3. [Accessed 17 Feb. 2018].

Wilson, M. (2014). IBM Invests $100 Million To Expand Design Business. [online] Available at: https://www.fastcodesign.com/3028271/ibm-invests-100-million-to-expand-design-business. [Accessed: 16 Feb. 2018].

Wodtke, C. (2017). How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love Design Thinking. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@cwodtke/how-i-stopped-worrying-and-learned-to-love-design-thinking-f1142bab60e8. [Accessed: 17 Feb. 2018].